This (long!) post questions the effectiveness of an input-based teacher-education models and considers the extent to which experiential frameworks based on John Dewey’s ideas could be a viable alternative.

Ask any teacher what the whole point of teaching English as a foreign/second language is and, eleven times out of ten, you’ll get a full-throated, unequivocal answer:

“To enable students to communicate.”

The degree to which teachers actually subscribe to classroom processes that do promote communication is another story, of course. But I digress.

Now ask any teacher educator about the ultimate goal of “training” talks/workshops and you will probably get a wider variety of answers, with anything ranging from “demonstrate”, “inform” to “promote reflection” and, why not, “entertain.”

But these, I believe, are not terminal goals. They’re subsidiary aims. I take the view that the ultimate aim of any input session (whether it’s a talk or a workshop) should be to promote concrete, long-term changes in the teacher’s classroom behavior.

But experience has shown me again and again that it’s ongoing classroom observation and feedback which taps into teachers’ belief systems that will ultimately bring about concrete, observable change in the classroom. Talks and workshops, useful and enlightening as they may be, seem to operate at the periphery of the whole process.

So where does that leave us?

1. Snapshots from two input sessions

Perhaps it’s the very nature of input sessions that makes them relatively ineffective agents of classroom change. But relatively is the key word here. The way we plan and deliver our sessions can make them far more likely to start the sort of ripple effect that will generate long-term, durable classroom change.

Below are two snapshots from input sessions I’ve given recently. Read them carefully and, as far possible, try to put yourself in the participants’ shoes.

Session 1

a. I began this session by asking teachers to try a simple experiment.

“Work in pairs and take it in turns to say your telephone numbers out loud in four different ways:

– In your native language

– In English

– Back to front

– In the 99.999.999 format.”

(Before you read on, you might want to say your number out loud, too.)

b. Then I invited teachers to describe the experience, how they felt etc.

c. Finally we discussed how easy it had been to retrieve and say the telephone number in each case. Why was the processing speed so dramatically different each time if the number itself was the same? This laid the groundwork for the concept of chunking and, eventually, teaching lexical chunks.

Session 2

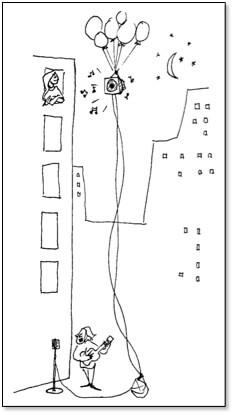

I started this session by proposing another simple experiment – the classic Bransford and Johnson balloons text (1972).

a. I split the group into two teams, A and B, and played the following text twice:

If the balloons popped, the sound wouldn’t be able to carry since everything would be too far away from the correct floor. A closed window would also prevent the sound from carrying, since most buildings tend to be well insulated. Since the whole operation depends on a steady flow of electricity, a break in the middle of the wire would also cause problems. Of course, the fellow could shout, but the human voice is not loud enough to carry that far. An additional problem is that a string could break on the instrument. Then there could be no accompaniment to the message. It is clear that the best situation would involve less distance. Then there would be fewer potential problems. With face to face contact, the least number of things could go wrong.

Team A looked at the accompanying picture while team B had their eyes shut throughout.

b. Then A and B teachers paired up and took turns reconstructing the text and describing the experience. Needless to say, team A teachers understood much more and were, therefore, better able to remember the text, which, not surprisingly, didn’t make much sense without the picture.

c. Teachers were then invited to discuss why the text proved so hard despite the lack of unfamiliar words, how the picture enhanced comprehension and so on. The ensuing discussion led us straight into the so-called schema theory + top-down processing and its impact on teaching the so-called receptive skills.

2. What’s behind these examples

The color scheme I used in section 2 reveals that the two examples follow essentially the same pattern:

a. First, teachers experience something first hand.

b. Then, they describe the experience.

c. Next, they draw abstractions from the experience and are introduced to the underlying theoretical framework.

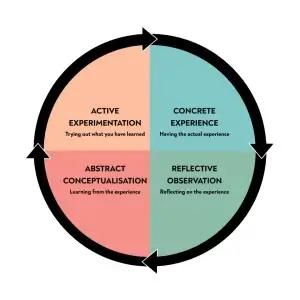

This model is based on John Dewey’s (1859-1952) views on the experiential nature of education, whereby students (teachers for present purposes) should be asked to deal with abstractions after rather than before going through relevant concrete experiences. Dewey’s ideas remain relatively popular to this day and have often been translated into a number of “experiential learning cycles“, made up of three or four stages each. David Kolb’s 1984 model is perhaps the most popular:

This sort of experiential learning framework stands in stark contrast with more traditional input sessions whereby teachers are first introduced to new concepts (“Let me tell you about task-based learning”, “Let’s talk about drilling”) and then shown real examples of those concepts. “Training” sessions based on experiential learning strive to make processes mirror content as much as realistically possible.

3. So what’s in it for teachers?

I’ve always been wary of establishing cause-effect relationships in education, but I’ll go out on a limb here and argue that input sessions based on experiential learning are perhaps more likely to bring about the sort of long-term classroom change I described in section 1. Maybe – and I say maybe – teachers who can not only observe and understand but also experience new concepts – right at the outset of the learning process – will be better equipped to notice and interpret the same phenomena in their own lessons and to make better sense of peer/tutor feedback, if and when it comes. In other words, input which is experienced and not only talked about is perhaps more likely to set in motion the sort of ripple effect teacher educators strive for (the last quadrants of the cycles in section 3, if you will).

4. Having said that

Not all input sessions lend themselves to the sort of experiential learning I’m advocating, of course. Not all theoretical constructs can be translated into useful, memorable, doable, or easily replicable concrete experiences. And that’s fine, really. ELT has had enough of one-size-fits-all solutions, I believe. But as a general sort of guiding principle, using Kolb’s cycle in teacher education makes an awful lot of sense.

So much so that in this article I chose to describe the two training sessions before discussing the theoretical model they were based on. I believe the article might have been harder to digest otherwise.

Thanks for reading.

I loved your article, Luiz Otávio. It goes hand in hand with what I myself advocate as a teacher “trainer” (if you allow me to use your quotation marks). I have always used experiential activities to reflect the ‘what?-So what?-Now what?’ cycle. However, one thing does make some of my neurons itch: How prepared do you think novices (ie people who have, to a certain extent, mastered the English language and are willing to teach it) are to cope with this sort of approach? I do have an opinion on that, of course, but I’d love to know what you think.

Thank you so much, Edmilson. And thank you for the question, which I’ve been giving a lot of thought to for the past hour or so. So, can novice teachers handle this sort of experiential approach? Yes and No, I think. Let me explain. First, the yes.

1. When you give an input session and your audience is made up of people who’ve been in the classroom for some time, they will all have a repertoire of concrete experiences to refer to. So, say you’re doing a session on top-down, bottom-up processing. Even if your session is devoid of concrete examples / experiences, most teachers will, somehow, try to anchor the new theoretical constructs to things they’ve done in the recent past – maybe even their last lesson. True, teachers’ experiences / belief systems will always be different and this means that it’s sometimes hard to make sure everyone’s on the same page. But the concrete experience will always be there, one way or another. Novice teachers who have little or no classroom experience to fall back on will be at a clear disadvantage here. This means that we could argue that it’s PRECISELY the novice teachers who need to go through concrete experiences the most. That way, it’s easier to make sure they’re all on the same page. Now, having said that…

2. We could also argue understanding certain theoretical constructs is not a priority for novice teachers. In other words, if you’ve never taught an EFL skills lesson, for example, all you need to know, at least initially, is that before you play the CD, you must set the context, the pre-listening questions and so on. You know, a sort of “follow the model” training paradigm, to equip novice teachers with the necessary skills to get by in the first few months, automatize certain classroom routines so that, down the road, they can engage in more systematic reflection. But having said that…

3. It could well be that concrete experiences don’t always HAVE to lay the groundwork for theoretical reflection. I’m thinking, for example, of a listening training session (for novice teachers) in which they’re invited to play the role of students in a very sloppy lesson (possibly in a foreign language) and then tell each other how they felt, what were the worst moments, what might’ve helped them learn better and so on without necessarily talking about schema theory, top-down processing etc. In other words, an experiential learning cycle where the “abstract conceptualization” quadrant is far less abstract.

Does that make any sense at all?

It certainly does make a lot of sense, Luiz; no doubt about that at all! Here’s the story: I and a great friend of mine (Paulo Kol, who now lives in BSB) taught, for several years in a row, no fewer than FOUR Intensive Two-Week Pre-Service Teacher Training Courses a year! What an experience that was, I’ll tell you… Our courses were aimed at teachers with little or no previous teaching/classroom experience. The overall goal of these courses was to equip (for the lack of a better word) teachers with the minimally necessary tools to enable them to plan a lesson, teach it and reflect on it.

The course was the result of / based on a wonderful experience Paulo and I had during a one-month-long teacher training course held in GYN. Mike Jerald, from the School of International Training in Brattleboro, VT, USA, was invited to be the main “trainer” then. Three other people (myself included) were co-trainers, in charge of different chunks of the course.

The thing that struck me as the most different/innovative aspect of the course was that ALL the sessions were based on experiential activities (you couldn’t have put any better when you gave the ‘listening training session’ example in your comment above). The whatever session we were teaching on the day always started with the teachers (the so-called ‘trainees’) having to engage themselves in some kind of “doing-it”, which was followed by “thinking-about-it” and then “re-doing-it” based on the insights/feelings/drawbacks/pluses drawn from the two previous sessions. As far as I understand, this is another way of wording the three cycles you mentioned in your great post: WHAT? SO WHAT? NOW WHAT?

Now, as I see it, the main reason why this course was such a huge success (apart from the fact that it was lead by Mike Jerald, an outstandingly competent professional), was the fact that ALL the participants were teachers who had been in the job for at least two years. Does this mean the course was doomed to have failed if the participants had been novices? Of course not!

Back to the training courses my colleague and I taught in the 80’s: After some 16-18 editions of the same course, it became clear to us that anyone willing to ‘prepare’ a person to step into a classroom and give a consistent answer to the question “What can my students do now that they couldn’t do before this lesson?” needs to find the balance between the amount of challenge (imposed by experiential activities) and spoon-feeding (the ‘survival kit’) novices usually need.

The point being? Fortunately, there’s no such a thing as the perfect recipe for teacher training (‘unfortunately’, others might argue). Fortunately, the main components of these sessions are human beings, whose needs/skills/gifts vary widely. Fortunately, some generous professionals choose to share their views and become bloggers.

Hi, Edmilson

What you described sounds like a wonderful learning opportunity for you and then, subsequently, for the people you taught.

There is, of course, a certain (inherent) tension between enabling a teacher to do something in class and fostering the kind of ongoing reflection that will promote long-term development. You know, learning how to, say, correct oral mistakes one the one hand and discussing the relative merits of oral correction on the other. Let’s call these A and B. Though A and B are not mutually exclusive, of course, there’s a certain trade-off here, isn’t there? How much time / attention / emphasis on A rather than B?

So, as you said, balance seems to be the key to success. Especially because the whole issue of teacher education is VERY context-sensitive. I think the EFL / language institute classroom, for all its diversity, is, at the end of the day, a very particular universe, with a fairly predictable set of players: 1. Students who need to learn how to communicate and “do” things with the language 2. ELT gurus who strive to find a way to make this happen 3. Schools that need to persuade these students that they can offer high surrender value – higher than the competition 4. Publishing houses that try to conflate 1,2 and 3 in the most profitable, user-friendly and, at times (though not always), dumbed down way possible and 5. Teachers with varying degrees of language awareness, experience etc. who, somehow, have to juggle 1,2,3+4 to keep their jobs.

So against this sort of backdrop, even if we try to be purely “developmental”, “descriptive rather than prescriptive” and “reflective”, some sort of “here’s how to do it” orientation seems inevitable. And I take the view that if we can pull this off experientially, so much the better.

Thanks for your comment. Really appreciate it.

BRILLIANT!

My preferred learning/teaching/learning style is a balance between input sessions and experiential learning.

Works for me and for most of the teachers I have had the chance to train so far.

Thanks for the food for thought.

Thank you, Ruymara. You’re right. Balance is key, isn’t it?

Hello! It’s my first time here, and I felt like sharing my view today…i totally agree with Ruymara and you regarding the balance between input sessions and experiential , but I also believe that it’s also up to the trainee to select the kind of training session he’ll sign up for. Every teacher should know How much he can absorb from a training session based on what he already knows about the subject. Of course it is so hard to guarantee that all participants will be on the same page when you deliver speeches in huge conferences, but to my mind, the best way to guarantee that the”trainer” will effectively provoke some kind of change in someone’s teaching habits is through class observation and feedback. If the trainer knows the Teacher’s strenghts

And weaknesses, he’s much more likely to hit the nail on the head, causing a real change in attitude from that teacher. In shirt, I believe that knowing your teachers is the key! Thanks for such an inspiring blog!

Alessandra,

Welcome to the blog and thanks for stopping by.

Interesting perspective.

I wonder, though, how many training sessions are explicit enough about the underlying processes for teachers to be able to make an informed choice.

Um abraço!

I agree that training is important. My daughter is taking up Spanish lessons right now and her teacher is very hands-on when it comes to studying. She’s very effective at what she does and it doesn’t matter what age her students are because she has a very good way of teaching her students.

Indeed, Martin. Most of these principles apply to language learning as well.